La influencia del arte mesopotámico en Miró.

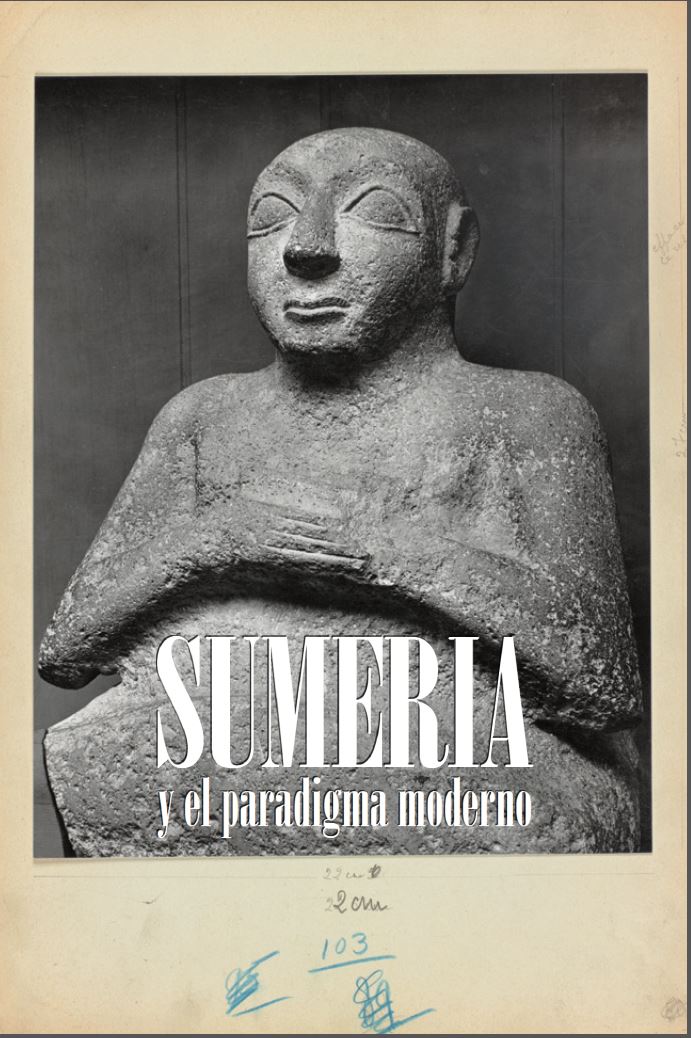

Gudea de Lagash. Col. Louvre, una obra sumeria admirada por Miró.

'Los diálogos del Louvre' son comentarios de célebres artistas en sus visitas al museo, recogidas por el crítico Pierre Schneider (1925-2013).

La influencia en

Miró del arte mesopotámico no se ha documentado bastante, aunque por las

entrevistas [Schneider, Pierre. Entrevista a Miró. Au Louvre avec Miró. “Preuves”, París, 154 (XII-1963)

35-44. FPJM H-3771. At the Louvre with Miró. “Encounter” (III-1965) 44 y ss.] y las fotos del archivo Miró

es seguro que se interesaba por la representación esquemática en los

bajorrelieves de las estelas y figuras sumerias y por la austera monumentalidad

de las estatuas de bulto redondo, sobre todo la de Gudea de Lagash. Destaca que

entre las ilustraciones colgadas en su taller en los últimos años estaba una

estatuilla mesopotámica sedente, la famosa escultura de alabastro del intendente

de Mari, del III Milenio aC de la col. Louvre. [<Joan Miró. Territorios creativos>. Las Palmas, Gran Canaria.

CAAM

(1997): 204.]

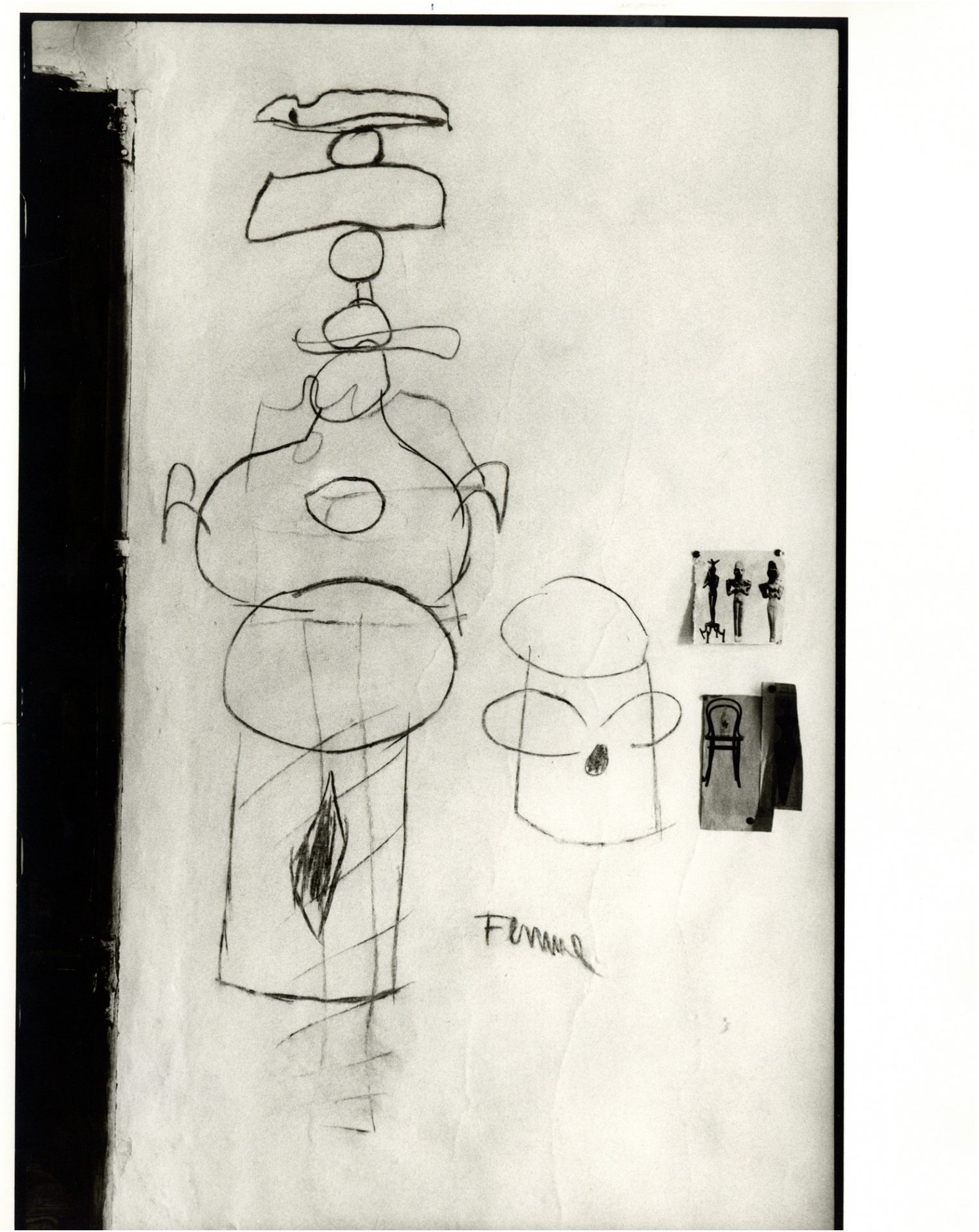

Baljeu (1958) analiza la pintura Mujer y pájaro delante del sol (1945) [D no cat. DL no cat.] y la

presenta como un ejemplo de la corriente abstracta (en la que incluye a Klee)

que se nutre de imágenes primitivas y sobre todo la interpreta como un

repertorio de símbolos mesopotámicos:

‹‹The painting by Miró Femme

et oiseau devant le soleil (Woman

and bird before the sun) contains the following symbols: the sun:

supreme judge; the woman: Innin, mother of the Herat, symbol of fecundity (see

the ellipsoid form on the body); the bird: the underworld, or death; the stars,

two evening stars: wisdom; the zigzag-line: fertility; and two signs of

probably biological nature. The disposition in space of sun-woman bird (the

diagonal suggesting a first, second and third plane) is most remarkable, as it

bears a striking resemblance to the Mesopotamian representation of heaven as

the realm of the sun (highest deity), below it the earth rising from the waves,

below that the underworld in the lower waters —also a representation in three

layers—. This painting thus stresses like again under the Klee as which Miró,

but restricted by Dalí and Tanguy to the nature of man (the subconscious),

reveals the wish to restore the relationship with nature, as a reaction to the

estrangement between man and nature ever since ancient Greek and nearly

Christian civilisation. It is only logical that Klee and Miró should revert to

Oriental forms, for the East never lost sight of man’s kinship with nature.

Yet, what primitive man realized unconsciously, they tried to imitate

consciously.›› [Baljeu. Mondrian or Miró. 1958:

14-15.]

Foster; Krauss; Bois; Buchloh (2004) sugieren las afinidades, que los

recursos técnicos de la fotografía nos revelan, entre las esculturas de Miró y

las figuras de terracota sumerias. [Foster; Krauss; Bois; Buchloh. Arte desde 1900. 2006 (2004): 273.]

Marc Marín, en Miró: el impacto sumerio [*<Sumer y el paradigma moderno>.

Barcelona. FJM (26 octubre 2017-21 enero 2018): 119-125)] ha incidido en esta

conexión, recordando la visita que Miró y Pierre Schneider hicieron al Louvre

en 1963 en la que el catalán muestra su admiración por el arte más simple de

Mesopotamia.

*<Sumer y el paradigma moderno>. Barcelona. FJM (2017-2018). Siete minutos.

*<Sumer i el paradigma modern>. Barcelona.

FJM (27 octubre-21 enero 2018). La historia de la recepción del arte y la

literatura de Sumeria en el arte de Occidente, a través de exposiciones o

revistas como “Documents” o “Cahiers d’Art”: Willem de Kooning, Barbara Hepworth,

Henny Moore, Alberto Giacometti, Joan Miró o Henri Michaux. Comisario: Pedro

Azara. Cat. Textos en catalán (trad. al inglés en pp. 145-166) de Azara; Pedro.

Elegia sumèria (13-115). Marín, Marc.

Miró: l’impacte sumeri (119-125). Pedde,

Brigitte. El Pròxim Oriente en l’obra del

pintor alemany Willi Baumeister (127-134). Bahrani, Zainab. L’art sumeri i l’avantguarda (135-143).

183 pp.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario